This is the first article in the Good Math Habits series, which aims to promote and nurture effective habits among young math learners, primarily those in elementary schools.

A Child’s Scratch Work Speaks Volumes

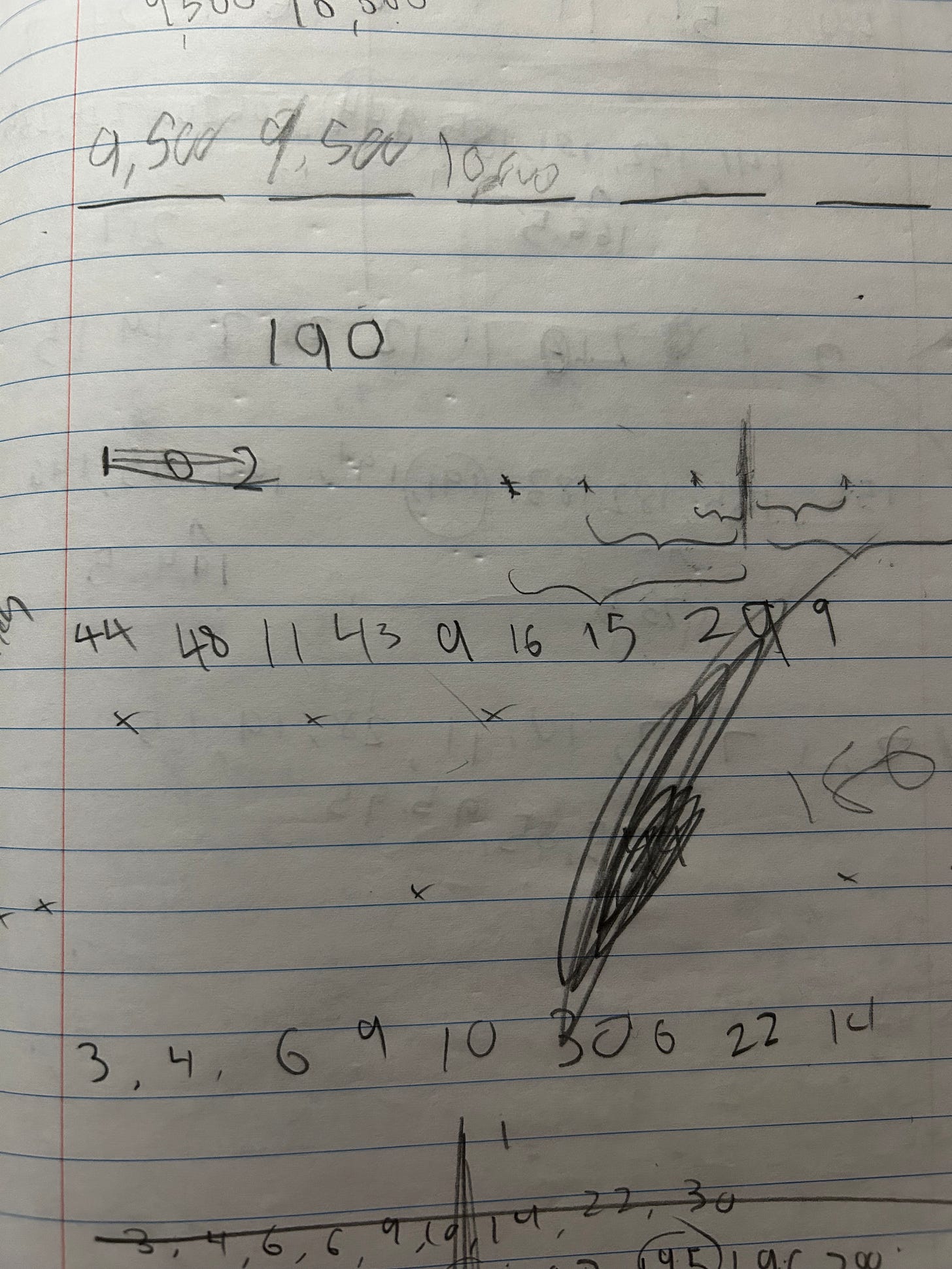

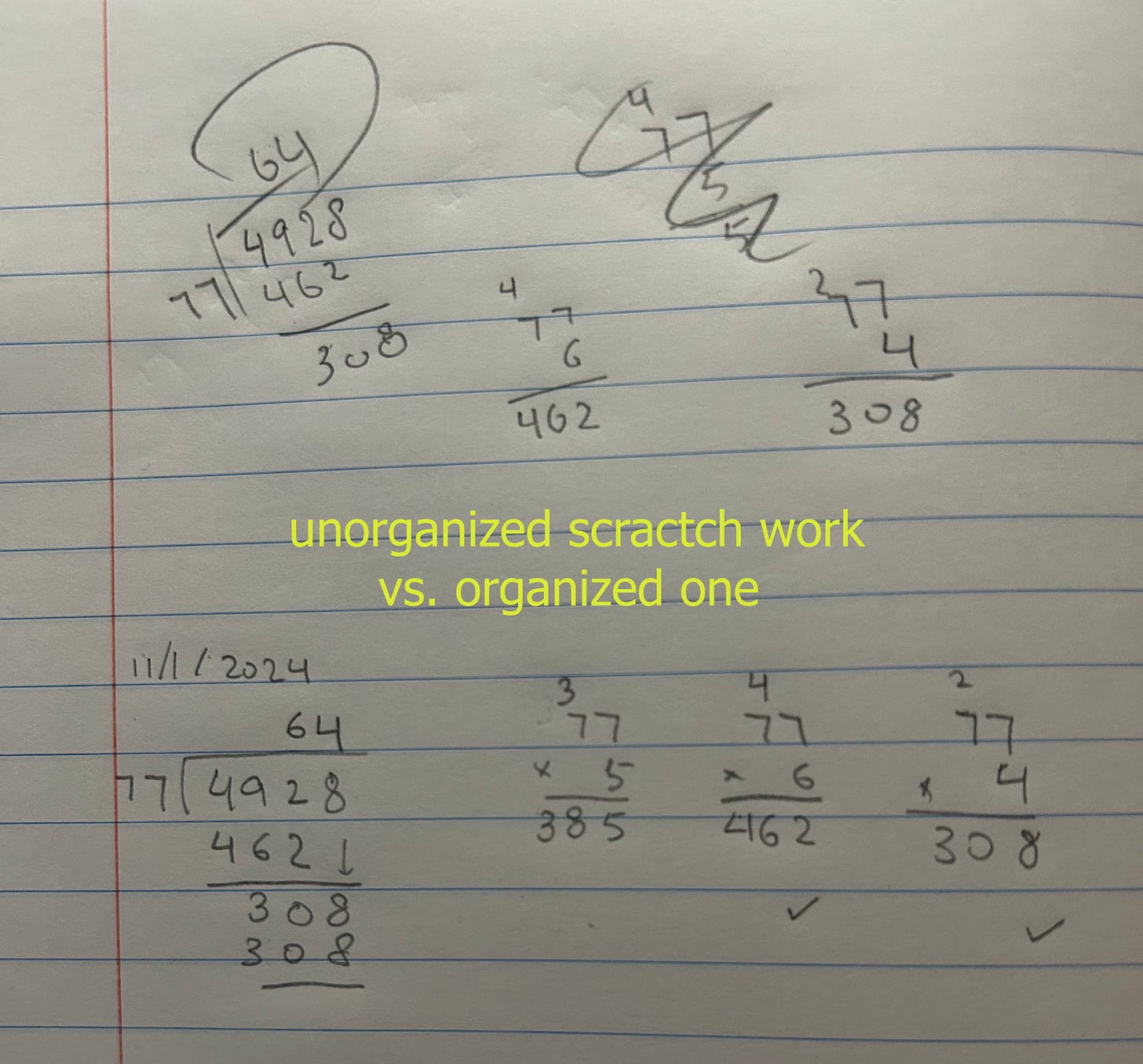

Let me start with a personal story. During the pandemic, much of my then-5th-grade daughter’s math homework was given in the form of multiple-choice questions through various learning apps. For these questions, all she needed to do was find the correct answer, and her scratch work was not submitted to the teacher in any way. Much of her scratch work looked like this:

You don’t need Sherlock Holmes to recognize that when a child writes in random directions with uncontrolled and even frustrated pen strokes, it is clear that they are not focused, not prepared, and, most importantly, lack “math confidence” when faced with the problem at hand.

A Blank Space Is a Brain Map

I’m not sure if you’ve had the same experience, but when I was young, staring at a blank space on paper could trigger mild anxiety. I didn’t know where to look or start writing, and as I wrote, I was constantly worried that my writing wouldn’t form a straight line, something I found unbearable.

For children, working through a math problem on their own represents significant cognitive and psychological growth. As they gradually fill the blank space with their calculation steps, they are essentially presenting their reasoning to the world. Scratch work, despite its unfortunate name, is a map of their thought process. It shows the details of how they connect and build abstract concepts and construct logical reasoning. It can also serve as a valuable tool for self-correction and growth. With adults’ guidance, children should develop the habit of reviewing their scratch work, recognizing how much they’ve grown, feeling proud, and building math confidence.

As adults, we may not have thought about this before, but careless or insensitive handling and comments on children’s scratch work can unintentionally create significant psychological barriers to their learning. Whether they are cognitively challenged or gifted, every child faces their own psychological hurdles when confronting a blank space and deciding where to begin. The least we can do is emphasize that this space is sacred and valuable.

How to Teach Children to Value Their Scratch Work

Make the message clear:

Teach students from the start that:

Their math scratch work is just as important as their math textbook.

Spotting and correcting their own mistakes is a skill they will learn to develop. Present the concept of “mistakes” with a sense of neutrality. Too many children carry an unnecessary sense of shame due to the frustrations they encounter with math in school, and this is entirely avoidable.

Scratch work is not just for teachers to grade. Even when they don’t need to submit their scratch work, they should still do it properly to guide themselves toward clarity in thinking and to avoid mistakes.

Establish basic rules:

I hate rules, and you hate rules, but I’ve learned that a few basic guidelines can effectively convey the message that math scratch work has value.

Here are some useful examples:

Ensure all writing is legible.

Date your work.

When working on a blank, unlined space, try to write as if following invisible lines.

Keep the spacing between numbers even and consistent

Don’t Trash Scratch Work:

Teach children to treat their math scratch work with the same care as their drawings or paintings. Whenever possible, use a lined notebook for their math studies and scratch work, and keep that notebook in good condition.

Looking Ahead

In the next two articles, I will provide suggestions on how to maintain neat and organized math scratch work, as well as how to handle mistakes effectively. The main long-term goal is for students to develop the habit of reviewing their own mathematical reasoning, recognizing their strengths and weaknesses, and guiding themselves toward growth.

Until next time, let math shine your thoughts and build your life.